One of the challenges for the semiconductor industry over a significant time period has been finding workers who have the right skill set for design, process development, and working in the fab. According to McKinsey, there will be a shortage of between 59,000 and 146,000 workers by 2029. Deloitte predicts the semiconductor industry will need over 1,000,000 skilled workers by 2030.

The semiconductor industry is not alone in the dilemma of finding skilled workers. In the U.S., businesses in nearly every industry are complaining of shortages in qualified workers for all sorts of job openings, including dishwashers. Although the crisis has softened a little as the unemployment rate continues to creep up.

Ironically, the most surprising news items of late, given the semiconductor job crisis, are the announcements of layoffs by several major players in the industry: Intel, Samsung, and Infineon. Additionally, major technology companies such as AWS, Cisco, Microsoft, and Google have laid personnel off during 2024. If the economy continues to slow, additional layoffs are likely.

What is creating this workforce paradox?

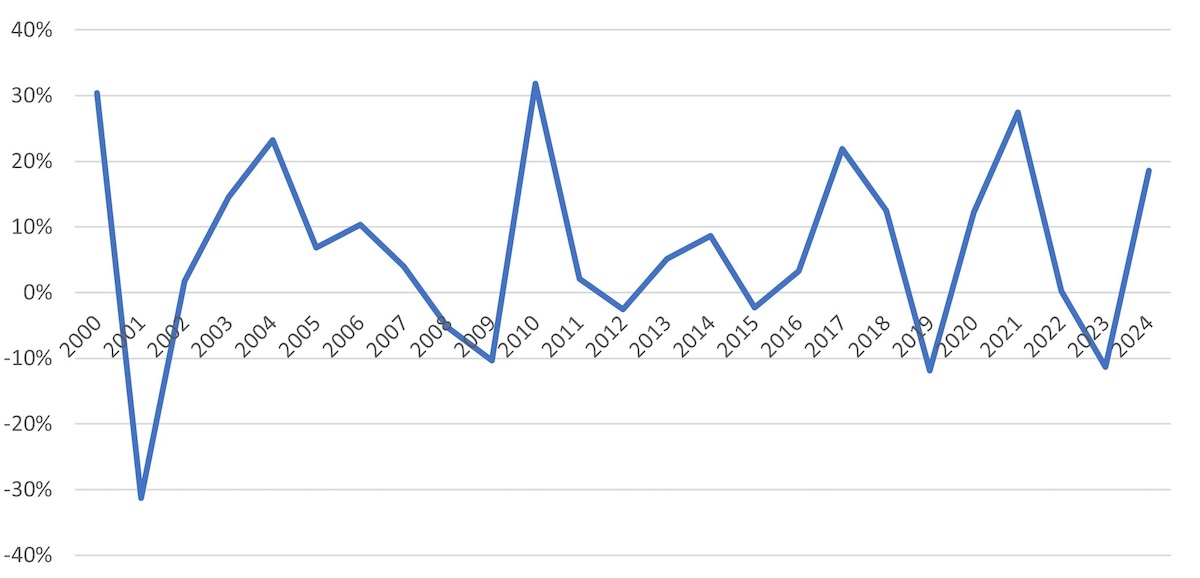

Having worked in the semiconductor industry for more than a few years, I’ve noticed that almost as consistent as the three-year semiconductor cycle is the layoffs that accompany it. In the 1970 and 80’s, each time there was a memory oversupply due to a PC slowdown, personnel cuts would be made. Some companies chose to reduce salaries to avoid or minimize layoffs.

The job-cutting methodology varied from the GE management methodology of cutting the bottom 10% of performers, to those smaller companies that had to make critical cuts in personnel. Part of the impact was that individuals new to the semiconductor industry made a career decision to hopefully find a less volatile industry (Figure 1).

Another emerging challenge for the semiconductor industry has been finding individuals who are receptive to working in a fab. A significant amount of press has circulated about the work environment or culture at TSMC’s Phoenix fab, with many long hours expected from the employees.

In the dark ages many fabs required ¾ and some still do ¾ four ten-hour work days. At one of the fabs I worked at, a 10-hour day was the norm, and if your equipment was offline or there was a process problem, you were expected to get it fixed ASAP. This might have meant a Saturday or two on occasion was spent getting everything up and working to keep the production line running. Fortunately, there are those who thrive in the fab environment and look forward to the problem-solving challenges that arise daily.

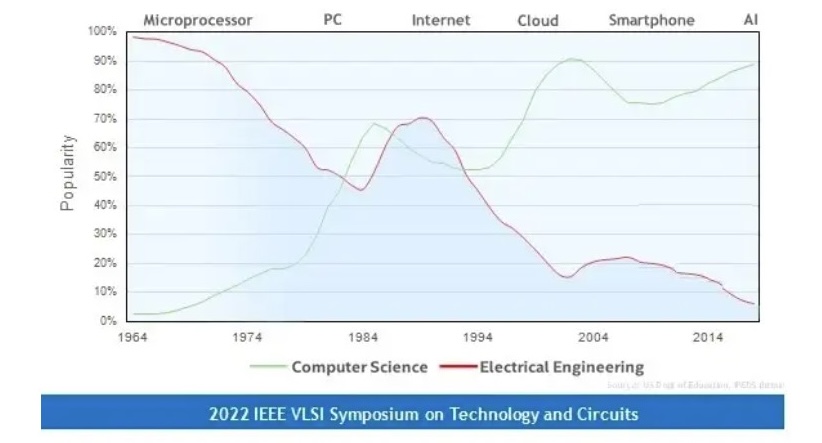

Another challenge the semiconductor industry faces is the declining rate of students enrolling in electrical or semiconductor engineering classes. During the years when scaling was key, chip design was based upon shrinking the previous generation and there was less material development taking place.

Hard science students moved into other disciplines and computer science became the cool degree. The chart in Figure 2 only tracks up to 2015, for a conversation that took place in 2022. So, with the need for new materials, and new chip designs as AI and quantum computing take center stage, hopefully, the needle is turning, and students will again take interest in semiconductors and the materials required for advanced semiconductor technology.

Universities such as Purdue, Arizona State, UT Austin, NC State, Georga Tech, Stanford, and others have had long histories of turning out semiconductor engineers. Kyle Squire, Dean of Fulton School at ASU stated at the ASU SWAP HUB award in September of 2024. “right now the fall semester is upon us we enrolled almost 33,000 majors in engineering in our college”.

The universities have developed new engineering programs to address the need for additional engineers. Junior colleges have developed programs to educate technician-level workers that are needed by the industry. Part of the CHIPS Act included funding for multiple university programs to focus on key semiconductor topics viewed as critical to the industry. This will hopefully result in a highly skilled semiconductor workforce that can propel the US industry forward.

Intel has created an apprentice program to help train technicians and operators to run and repair equipment in the fab. The development of an apprentice program returns to the older days of the industry where a few companies would hire physicists, chemists, chemical engineers, and electrical engineers and train them on the job. Texas Instruments was nicknamed “Training institute” as they had a very thorough training program for new engineers to bring them up to speed on chip technology.

Companies such as Tokyo Electron, under the guidance of Larry Smith, was one of the first companies to reach out to the military to provide job opportunities and training to service people who were transitioning from the military to civilian life. This hiring avenue appears to be working well for TEL and will hopefully transition across the rest of the industry.

When some of the first studies on industry shortages started to pop up, SEM Foundation, under the guidance of Shari Liss, ramped up SEMI University from a few training programs to a comprehensive industry training system. SEMI Foundation created STEM programs in grade school to semiconductor and robotics programs for high schoolers that will hopefully pique their interest in a career in semiconductor and electronics technology. For its members, SEMI has developed training programs in multiple languages that cover a wide variety of semiconductor industry topics. This ensures that the training target is worldwide not just regionally located.

When the alarm was sounded academia and the semiconductor industry responded very rapidly to the training needs of new engineers and technicians for the industry. What we can hope for is that the current round of layoffs will be short-lived and that the new factories will stimulate the demand for the individuals that are currently being trained to fill these factories of the future.