Someone once asked me if the circular economy requires a specific type of currency. Let’s clear up some basic misconceptions. The circular economy:

- Has nothing to do with cryptocurrency

- Relates to how we extract and use materials to make products

- Stands in contrast to decades of growth in the linear economy

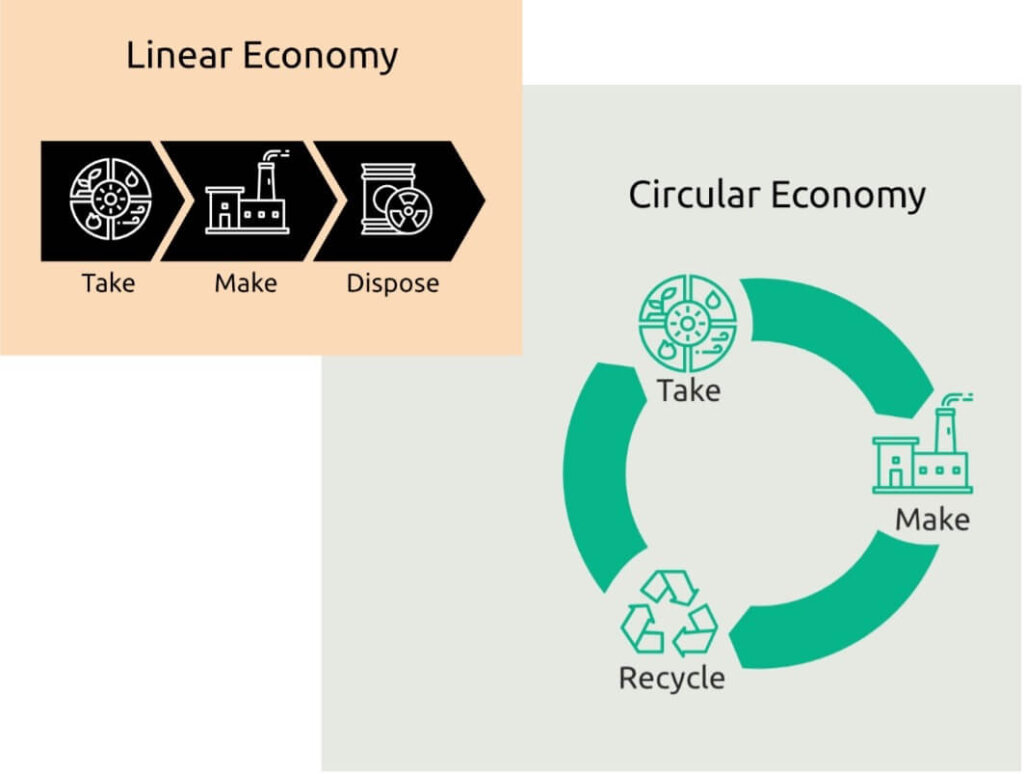

The diagram below illustrates the basic concept. The circular economy replaces the model of “take, make, dispose,” with the model of “take, make, recycle.” There is a lot more to it, and you can find much more detailed diagrams, like the classic one from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

How can we move from linear to circular? If it were easy, industries around the world would have done it by now. This blog post will offer insight by considering:

- The linear economy and semiconductor manufacturing

- Circular economy practices and the definition of zero waste

- How to look at your company’s position and propose suggestions

Semiconductor Manufacturing and the Linear Economy

The linear economy depends on products being created, used, and disposed of. It drives the production of new materials and new goods and assumes that all economic growth is desirable.

The semiconductor industry has relied on a linear economy model for decades. Moore’s Law—the infamous “rule” that the number of transistors per unit area of silicon will double every two years—has inspired the drive toward making microprocessors smaller, faster, and cheaper.

The resulting innovation has been impressive. More computing power than was available in room-sized machines 50 years ago now resides in devices we hold in our hands.

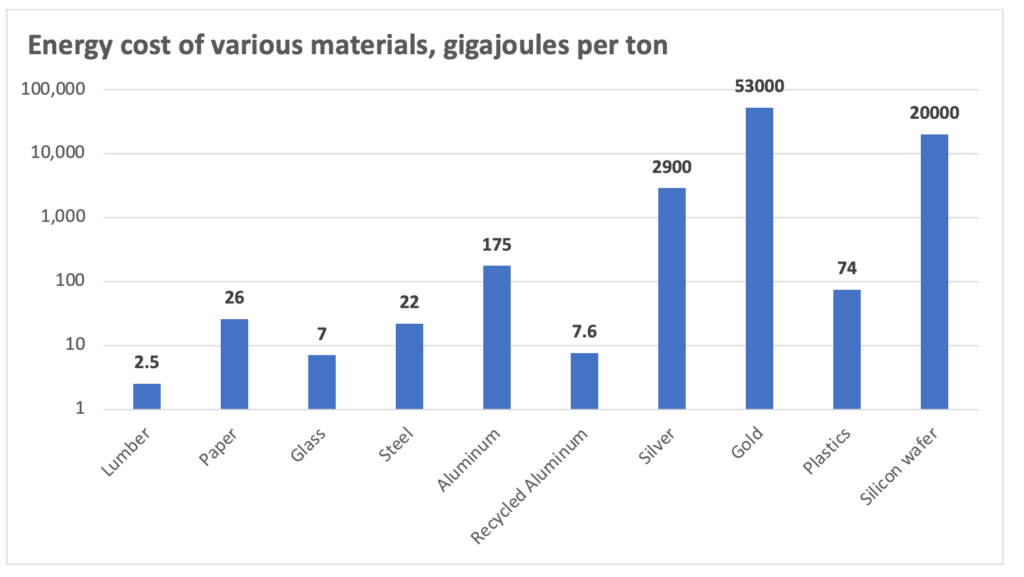

Our electronic devices benefit society in multiple ways, but what about the environmental damage associated with their production? Considerable energy is required to produce silicon, copper, gold, and other materials that make up a semiconductor chip.

The original source of most of these materials is from mining metallic ores. Mining is dirty work that requires caustic chemicals, exposes workers to dangerous conditions, and pollutes the surrounding communities. It produces far more tons of toxic waste than usable metals.

The environmental impact reaches beyond the materials that end up in a computer chip. Standard subtractive patterning processes remove materials deposited on the wafer and often do so with toxic strippers and etchants.

Spin coating of polyimides is an inherently wasteful process. Over 90 percent of the liquid that is deposited on the wafer spins off. The excess usually ends up as hazardous waste. While it can be filtered and reused, the cost of filtering to the required purity levels deters fabs from choosing that approach.

There are opportunities to make semiconductor manufacturing less linear and more circular, and some companies are moving in that direction. The path forward, unfortunately, is full of obstacles.

Making it Circular: Toward Zero Waste

In the circular economy, everything is part of either an organic cycle, where compostable materials return to the soil, or part of an inorganic or technical cycle, where materials like plastics, glass, and metals are recovered to make new products.

An economy that is 100% circular allows no waste. Although the laws of thermodynamics preclude infinite recycling with no loss of mass, it is possible to approach the goal of recovering all raw materials used in manufacturing.

As a step toward the lofty target of 100% circularity, companies can pursue Zero Waste to Landfill certifications. Multiple organizations offer these certifications. Brewer Science, for example, has been certified Zero Waste to Landfill through GreenCircle since 2016. It claims to be the only company in the semiconductor industry to have achieved this certification.

While there is no universal global agreement on certification requirements, the general concept is to send nothing to the landfill. Companies can achieve this goal through a variety of approaches. The strategy will probably be different for each waste stream.

In the past few years, more semiconductor manufacturing companies are pursuing Zero Waste to Landfill. This is encouraging news. Data from 2020 sustainability reports shows that there is plenty of room for improvement, though. Recycling rates at many companies with decent environmental ratings range from 55 to 95%, and some of the laggards probably recycle a much lower percentage.

The recycling rate is, of course, not the only or even the best metric to consider. It is important to look at total waste generation. KLA, for example, reported a drop in recycling rates over a recent six-year period but noted that total waste generation dropped.

In the common phrase, “reduce, reuse, recycle,” the words appear in that order for good reason. The priority should be to reduce the amount of waste a company generates. That can involve everything from small changes like not providing disposable coffee cups to overhauling a manufacturing process to reduce or eliminate the need for certain solvents.

There are many opportunities for reuse within a factory or a fab. Facilities can filter wastewater and process chemicals and put them back into the manufacturing flow rather than releasing them into the local environment.

While setting up such a process involves capital expense, the savings in operational costs will probably pay back the investment in a relatively short time. Water use will decrease. In the case of process chemicals, companies can avoid the expense of hazardous waste handling permits. The solid residue collected in filters might not be classified as hazardous.

Sometime reuse involves selling or donating scrap to a different industry where contamination or reliability requirements are not as stringent. From a semiconductor industry perspective, this approach can run both directions. Scrapped silicon wafers can end up in solar panels. Excess carbon fiber scraps from the aerospace industry can go into laptop housings.

Recycling is something that nearly all companies are doing already. Breaking down cardboard boxes that come from suppliers and recycling cans and bottles in the cafeteria is standard practice. Many items that are not commonly thought of as recyclable can, however, be recycled. You may be surprised to learn that used cleanroom garments need not end up in a landfill.

If you improve sorting of potentially recyclable materials in-house, more of the waste that you cannot reuse can enter the municipal commercial waste recycling system. Proper sorting is the critical piece since the more uniform and consistent the waste stream, the more money a waste hauler can get for selling it.

Incinerating, or converting waste to energy, should be a last resort. While it is an allowed method for achieving zero waste to landfill, burning mixed waste creates toxic ash. That said, systems that convert waste to energy and use that energy to power equipment within the same building can be a valid part of a complete Zero Waste to Landfill program.

What is Your Company Doing?

Where does your employer stand on circular economy principles? Does the term “circular economy” appear anywhere on your factory or office walls or on your website? Has your company set ambitious goals to reduce waste and find better uses for the waste it generates?

If so, congratulations! If not, you can still join the movement.

Upcoming blog posts in this series will discuss topics that are related to the circular economy. The next one looks at the supply chain. No company is completely vertically integrated. Steps to reduce waste must involve auditing suppliers and providing customers information to help them continue the cycle of reuse. At the end of the supply chain, better e-waste practices will give manufacturers more consistent sources of recycled metals.

It is also important to distinguish between hazardous and nonhazardous waste. The less of the latter you produce, the more easily your waste stream can be reused or recycled. As I discuss in Material Value, removing toxic chemicals from a process is not easy, nor is it always even feasible. But if government regulations or customer pressure forces a manufacturer’s hand, solutions can emerge.

As you consider how to make your employer’s operations more circular, everything from materials to product design to product packaging matters. Can you think of ways to move your company toward zero waste to landfill? By discussing ideas with your colleagues and your industry, you can make a difference.

Reply to this blog post to share what has worked at your company or what you think your segment of the supply chain can do to be more circular. When we talk about successes and voice suggestions, we build awareness that can inspire industry-wide change.